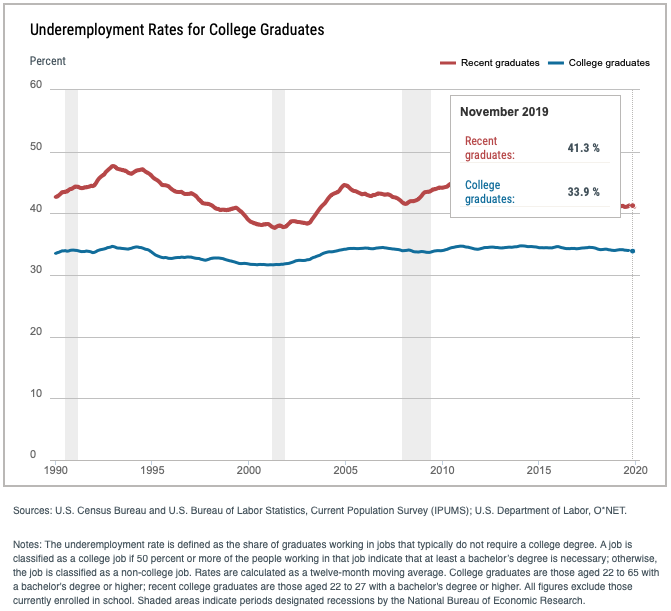

In Parts 1 and 2, sentiment amongst college students and prospective college students may already be declining, which could be exacerbated even further, as we weather the current global pandemic with closed college campuses and students dispersed to their childhood homes. Additionally, the last of the Millennials are now college graduates, but experiencing a current 41% underemployment rate, meaning they work jobs that do not require college degrees according the the Federal Reserve, which may decline exponentially given the current macroeconomic backdrop.

Now, the first of the Gen Z’ers are set to graduate (at least virtually) from college, engulfed by the Panic Pandemic of 2020, finishing the last of their classes online, evicted from their on-campus residences, their college experience summarily truncated. They enter the workforce for the first time confrotned by global economic upheaval not seen since The Great Depression. For many of the Class of 2020, the Golden Ticket seems like an ephermareal dream.

The Economist defined “The Golden Ticket” as:

…the “graduate premium”—the difference between the average earnings of someone with a degree and someone with no more than a secondary-school education, after accounting for fees and the income forgone while studying. This gap is often expressed as the “return on investment” in higher education, or the annualised boost to lifetime earnings from gaining a degree. Research by the New York Federal Reserve shows that the return on investment in higher education soared between 1980 and 2000 in America, before levelling off at around 15% a year. In other words, an investment equal to the cost of tuition and earnings forgone while studying would have to earn 15% annual interest before it matched the average value over a working life of gaining a degree.

The Economist, February 3, 2018

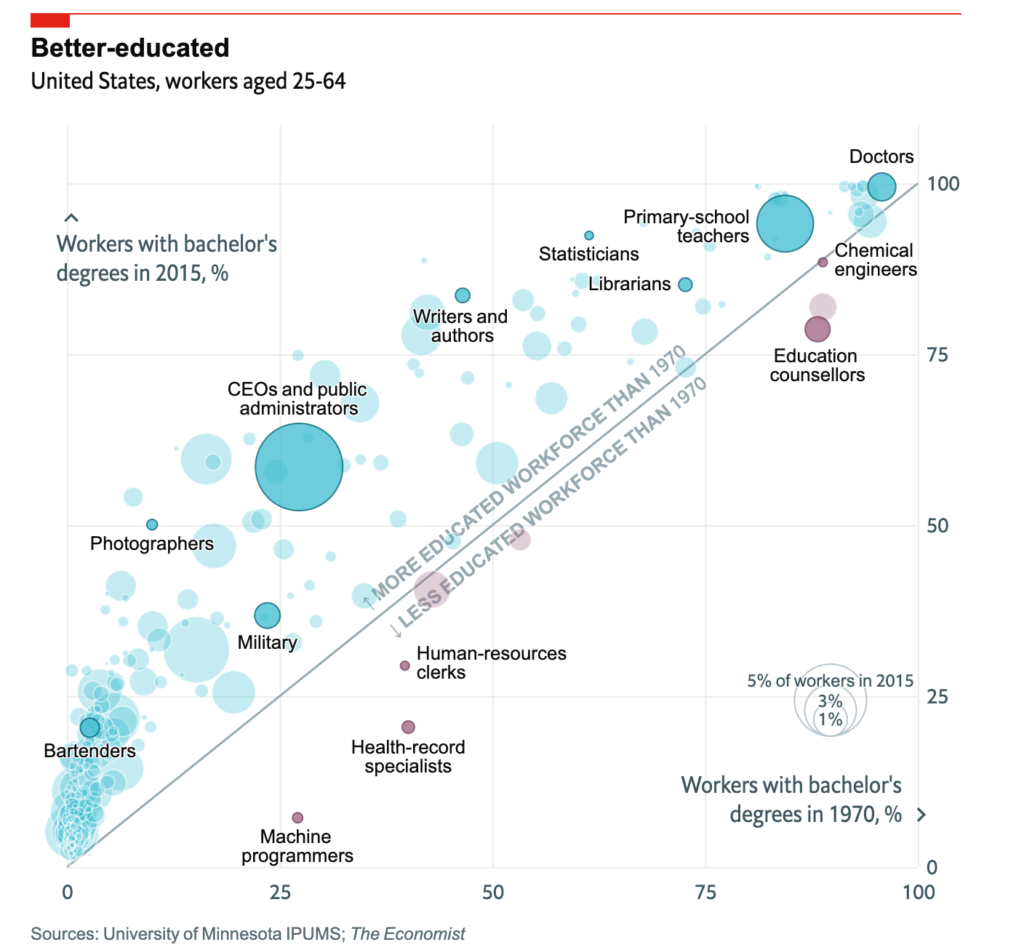

Yet, as more and more individuals, approximately 43% of 25-64 year olds in the United States, are college graduates, the value of their degrees are diluted. As Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic and Becky Frankiewicz recently published in The Harvard Business Review:

…the value added from a college degree decreases as the number of graduates increases.

The Harvard Business Review, January 7, 2019

And, data produced by The Economist only validates Mr. Chamorro-Premuzic’s and Ms. Frankiewicz’s logical deduction. The graph below visualizes:

Judging by job titles alone, 26.5m workers in America—two-thirds of those with degrees—are doing work that was mostly done by non-graduates a half-century ago.

The Economist, February 3, 2018

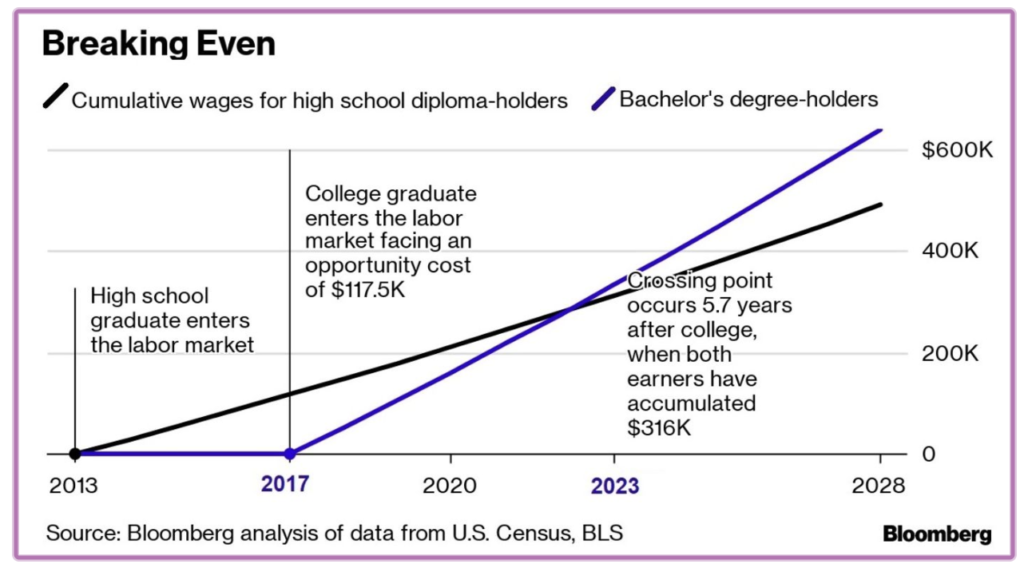

In other words, for at least four years, college-go’ers are postponing joining the workforce, forgoing income earned in those years incurring an “opportunity cost” (see graph from Bloomberg News below), which requires another 5.7 years to overcome.

Additionally, college-go’ers assume the costs of college—tuition, living expenses, books and supplies—which have been annually increasing at rates higher than inflation for the last three decades.

Since 1990 fees for American students who do not get scholarships or bursaries have risen twice as fast as overall inflation.

The Economist, February 3, 2019

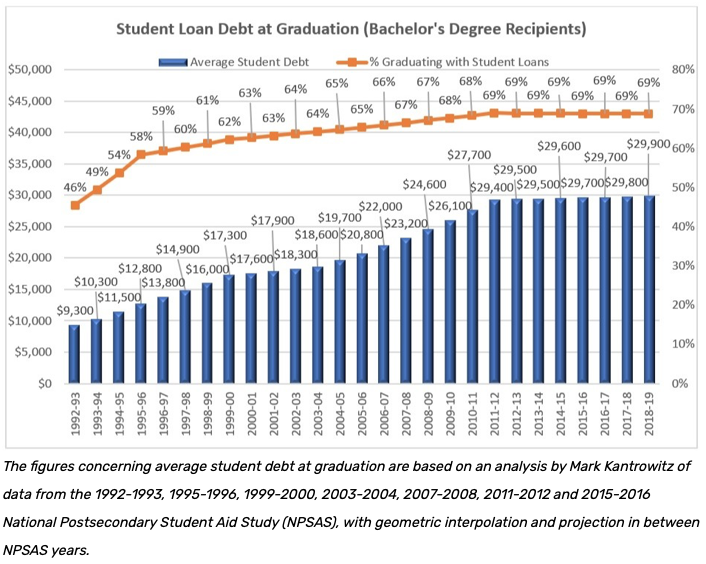

Thus, in the quest for the perceived economic premium of a college degree, college go’ers have willingly borrowed to pay for the increased costs. Coinciding with the increasing tuition, average student loan amounts as well as the percentage of college graduates with student debt have risen annually, so that nearly 70% of the College Class of 2019 graduated with an average $29,900 of debt.

Then adding insult to injury, when these same Millenial college graduates enter the workforce, only eventually be hired for jobs which have not, as recently as their parents’ generations, required a college degree.

And, as the promised economic prosperity seems less likely for Millenials approaching middle age, their angst is palpable:

The already-waning goodwill of students has been stretched even thinner in the recent months, due to the truncation of the college year effecting each cohort of students drastically, although differently. Without concerted and consistent communication between students and university officials, to reinforce the bonds between students and their colleges, not only will sentiment about college education continue waning, but college administrators may return to a reduced student body when campuses re-open.

Since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, the decade long inflation of college costs and college-going rates has diluted the value of a college education. Declining sentiment about college degrees calls for a thorough analysis, over a series of candid discussions about the value of college amongst all stakeholders, to address potential reforms in an attempt to prevent an irreversible decline in sentiment. Otherwise, the damage to the educational industrial complex, integral to an advanced economy as well as essential for improving the collective standard of living, may burden a generation or more.