An online, distance learning college education is not what most four-year college students and their parents paid (or borrowed) to experience. With college closures, the holistic “college experience” has been truncated, as entire university communities have been dispersed, with no late-night dorm floor existential debates, no clubs, no socializing—stripped down to simply content delivery through a screen. Additionally, faculty are now being asked to turn on a dime and transform their classroom-designed teaching style and curriculum into an effective online, remote delivered, distance learning forum.

Professors are humans, requiring time to adjust, just like students—where some will transition effectively and others will not. However, during the adjustment, a humility and a collective understanding that we’re all transitioning together is essential, so we can both sustain and refine the modern American university.

Even in normal circumstances, in order to teach, professors need the trust of their students—trust that the professor knows the subject they’re teaching and trust that the professor is adept enough to teach the subject to any other human. However, building that same relationship through distance learning requires another level of deft and potentially greater effort. Otherwise, professors risk alienating their students.

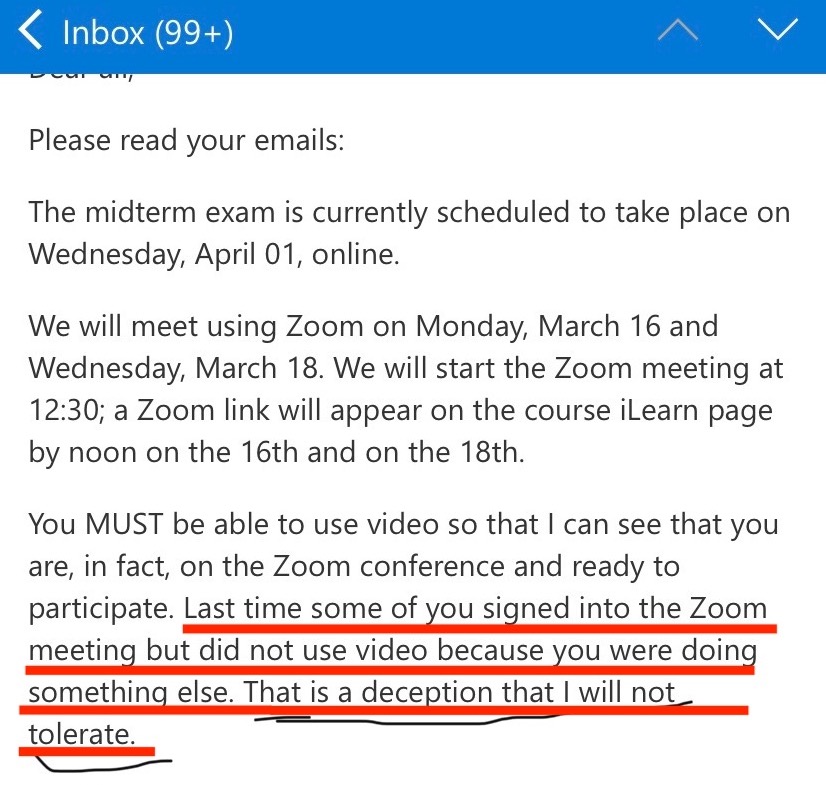

A California State University professor, who wrote the email pictured below, exemplifies how to break the trust of students:

The professor didn’t ask why students weren’t using their cameras, nor accounts for students who may not have cameras on their computers or may not have internet access that supports digital video. The professor simply accuses students of “doing something else”, drawing a conclusion without any discussion or due process. In making a definitive conclusion, the professor breaks the trust necessary for learning.

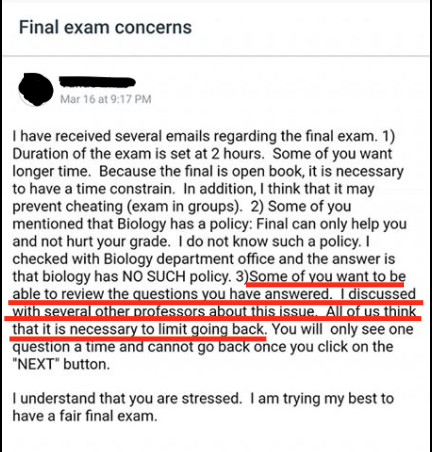

Similarly, in the email screenshotted below, a University of California professor’s inflexibility on amending the format of a final Biology exam sowed discord and did not account for the context in which his students were now testing. The professor misses that at the beginning of the week, his students were directed to proceed as usual, attending classes in-person and preparing for in-person finals, plus were assured they could remain in their on-campus residences. Then, by Friday, adminstrators moved finals online and encouraged students to move home for the remainder of the year, which many did.

Some Biology students requested a fair testing situation: the option to review test questions after answering and the full three hour final exam period, which is standard for in-person finals. However, pictured below is the Biology professor’s response:

The professor’s inflexibility neither reduces the opportunity for cheating, as cheating can occur online or in-person, nor creates a fair test for students.

Instead, the professor simply alienated his class, where one student then took to the internet, garnering 251 thumbs up, angry and sad emojis, plus 78 comments, posting the email pictured above. Now, at least 329 people in the Facebook group, bonded sharing similar frustrations about their now-online college education. Such experiences, add to their already-existing dismay and bitterafter taste about now living back in their childhood bedrooms, no longer experiencing the college education they had nor imagined.

Conversely, when professors are human, understanding the complex adjustments students are making, then not only do they build the trust of their students, they create a fairness in a virtual “classroom” where students can learn.

In the email below, one professor at a private university deftly both amends his coursework for the end of the semester, while maintaining the academic rigor, providing flexibility for students who are now dispersed around the world, as well as reinforcing their shared humanity. In being communicative, the professor, as a representative of the university, reinforces the trust between him, the university and the students.

Dear all,

I have spent the last few days, as I am sure many of you have, scrambling to figure out how to keep myself and my loved ones safe, and to figure out how to fulfill my responsibilities towards you under these extraordinary circumstances. In that spirit, I wanted to lay out my plan for how to manage this class in ways that take fully into account the varied pressures we are facing.

I want to state at the outset: my first and foremost concern is for your well-being, physical and mental. I want you to know that, in my capacity as an elected officer of the Main Campus Executive Faculty, a faculty governance body, I am here as a conduit for any concerns that you may have that I can convey to higher authorities in the university who may be better placed to address them.

In that spirit, I have decided to change my grading policies for this class. Not only will you be able to change your grade to pass/fail, right up until the end of the semester, according to new university accommodations, but for this course, I will consider the work you have done thus far as the basis for your grade. That means that anything you turn in henceforth will ONLY count if it improves your grade and will be discounted if it does not. This also means that I will not penalize you for not turning in assignments. Your first concern, as is mine, is your well-being and I do not want this course to present any additional stress to you. Do only as much as you feel like doing.

That being said, in the spirit of inquiry that brought our classroom community together in the first place, the rest of the course will continue in terms of topics according to the schedule on the syllabus. Given that not all of you will have equivalent access to the internet for our transition to virtual learning, I have put together a plan at least for the next few weeks that I hope will be practical. Starting this coming Monday night, I will post detailed lecture notes ahead of our usual Tuesday lecture meetings that I hope you will peruse. I encourage you to use the discussion board I set up to jot down questions that arise from the lectures/readings that I would normally have answered on Tuesday itself. On Thursdays I will set up a Zoom meeting for us during our usual meeting times. (I m sure I will make mistakes with the technology- bear with me, this is as new to me as it is to you.) Again attendance is not mandatory, given differences in time zones and varied internet access. Instead, I’d like you to think of these classes like extended office hours when you can check in whenever you like to talk to your classmates and to me. I encourage you to do so mostly because I think community is an important resource in such times and we are a community- a temporarily constituted one for sure, but a community nonetheless.

Lastly, as a historian, it is incumbent for me to point out what an extraordinary event we are living through. In our last meeting, I mentioned the historical precedent of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic for thinking about what is unfolding around us. (I encourage you to read this essay on how it may have specifically effected the events in South Asia we have been studying: https://caravanmagazine.in/history/spanish-flu-1918-changed-india) Recently, as people on social media have been posting the reminiscences of deceased or very elderly relatives who survived that pandemic, including the local vernacular names for it, it occurred to me how much of the potential archive of that pandemic has been lost especially in South Asia. In that spirit, I want to ask you to keep a diary of the coming few days, reflecting on how this pandemic is affecting the community/locality where you find yourself. Record how people in your circles talk about it, what anxieties they express, what social cleavages this emergency may have revealed to you. At the end of this course, I’d like you to upload your diary into a repository that I hope to preserve as an archive of COVID-19. Given that I cannot offer the support I normally would to help you complete your final research projects, I will consider this your final assignment for the course instead. (Of course, you are welcome to continue to work on your original research projects and I will read them with great interest. Again, I would only count it if it improves your grade.) I hope this project will reduce the pressure on you but also make you think about the discipline of history from a point of view one rarely considers in an undergraduate course: that of the work of archiving and preserving historical evidence for the future.

With best wishes for your well-being and for your loved ones,

All italics are Creative Marbles emphasis

As faculty are on the frontlines of maintaining students’ connections with their universities during these extraordinary times, as the people communicating most often with them—whether desired or not—professors’ roles as university ambassadors, community builders, public relations officers become heightened. Yet, additionally, they continue fulfilling their primary responsibilities as teachers, counselors, and role models.

The goodwill of students is being stretched, as university communities are no longer centralized, where everyday interactions reinforce community membership. When professors are fair and flexible, how is that not a win for everyone in both the short term, but also for the longevity of the university?

Otherwise, university administrators, staff, and faculty risk alienating an entire generation of students, whose lives have been oriented to obtaining a college education. From pre-K, they weren’t asked, “Are you going to college?” but “Where are you going to go to college?” They subsequently developed a consciousness about their activities and decisions, as in, “How will this benefit my college resume?“

Now, they’ve been summarily evicted from college campuses, separated from their networks of friends, professors, clubs, internships, research-ships, the list continues, and while surounded by family, they’re merging two worlds—childhood home and college “home”—while still learning complex topics, with all the attendant worries about graduate school, grades, declaring majors, summer internships that have been cancelled, on top of existential concerns about life and death.

While not diminishing the pressing health emergency, university officials and particularly faculty, also must remain vigilant, acting mindfully, knowing their actions today will impact the viability of the university in the long term. With skillfulness, faculty and university adminstrators will fulfill their duties as leaders and the influencers of young minds, reimagining the college experience to preserve the value of a college education.